Hidden present hearts - Les cœurs cachés et présents

Église Saint-Bruno les Chartreux, 56 rue Pierre Dupont, Lyon, France

13 September - 7 October, 2017

Exhibition photos: Sandie Magnan, James Murnane, and Philippe Dumont --- Artwork photos: Tony Fuery.

Les cœurs cachés et présents

Le baldaquin mouvementé de Giovanni Niccolò Servandoni étonne peut-être parfois les fidèles et les visiteurs de l’église Saint-Bruno les Chartreux de Lyon. Les effets du baroque, même parfaitement maîtrisés, semblent en effet avoir peu en commun avec la spiritualité cartusienne, son quotidien de silence et de prière, ses règles immuables. Les stalles, les sièges de bois des frères situés de part et d’autre du chœur, marquent d’ailleurs encore la présence ancienne des Chartreux sur le plateau et les pentes de la Croix-Rousse. À l’initiative de l’Ordre, les travaux de l’église débutèrent à l’orée du XVIIe siècle. Elle deviendra église paroissiale en 1803.

Dans ce bel écrin blanc et doré, serein et subtil, rare exemple de baroque dans la ville, il émane de ces majestueux sièges vides quelque chose d’énigmatique et comme une question posée à notre époque volontiers frénétique, toujours en quête de réponses rapides, de bruit et d’originalité. À l’inverse, sans mot dire, ces vies, passées et présentes, retirées, loin de tout en apparence, interrogent encore. Malgré leur absence depuis la Révolution à la Croix-Rousse, la prière des Chartreux irrigue toujours le monde de son irréductible singularité. C’est ce courant secret qui a inspiré à l’artiste James Murnane son projet accueilli aujourd’hui dans l’église. Mais comment rendre visible l’invisible ? On se souvient des silhouettes mystérieuses filmées par Philip Gröning dans Le Grand Silence. On y voyait, comme au ralenti pour nos yeux habitués à d’autres vitesses, le quotidien de moines plongés corps et âmes dans l’anonymat et la quête spirituelle au cœur du massif de la Grande Chartreuse, près de Grenoble, qui a donné son nom à l’Ordre créé par saint Bruno.

Par la grâce d’une rencontre avec l’abbé Matteo Lo Gioco, curé de la paroisse, James Murnane donne à voir d’une tout autre façon au sein de l’édifice lyonnais quelque chose de ces mouvements secrets du cœur et de l’esprit grâce à sa proposition intitulée Hidden present hearts - Les cœurs cachés et présents. Les petites peintures sur bois de magnolia japonais, chacune nommée « un cœur » (A heart), sobrement posées sur les stalles, viennent signifier à la manière d’icônes la présence priante d’un frère d’hier ou d’aujourd’hui, d’un cœur présent caché. Car pour répondre au retrait du monde incarné par la vie monastique, ou, plus exactement, pour lui faire signe, James Murnane a ici mis en œuvre volontairement une certaine pauvreté de moyens. Devant ces surfaces peintes de dimensions modestes, il faut en effet tout d’abord oublier ce que montraient les images de Philip Gröning avec un grand pouvoir de suggestion, et même de fascination : l’ample habit blanc des moines, les gestes du travail, de la liturgie, la solitude paradoxale de visages habités, la neige au matin... D’une manière diamétralement opposée, le « manque d’image » qui fonde la peinture abstraite représente peut-être pour nous une chance supplémentaire de comprendre la curieuse géographie des Chartreux où la clôture même, contre toute attente, est la gardienne de la plus grande ouverture au monde. On peut sans doute approcher ainsi du regard cette peinture qui se refuse à figurer directement pour préserver notre propre pouvoir de regarder, de créer des images, sans se soumettre à aucune. L’abstraction, comme la vie monastique, serait donc tout d’abord synonyme de liberté intérieure.

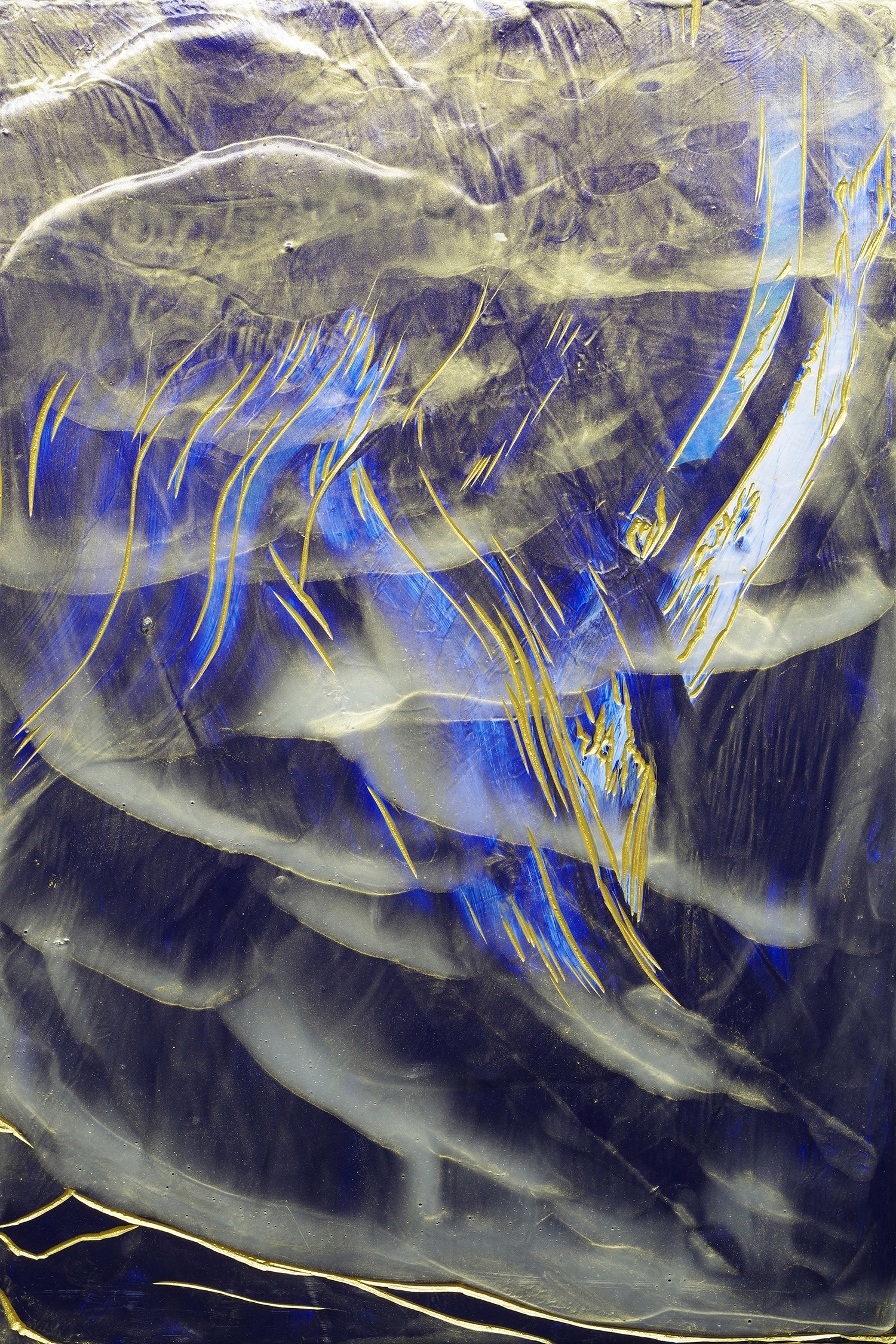

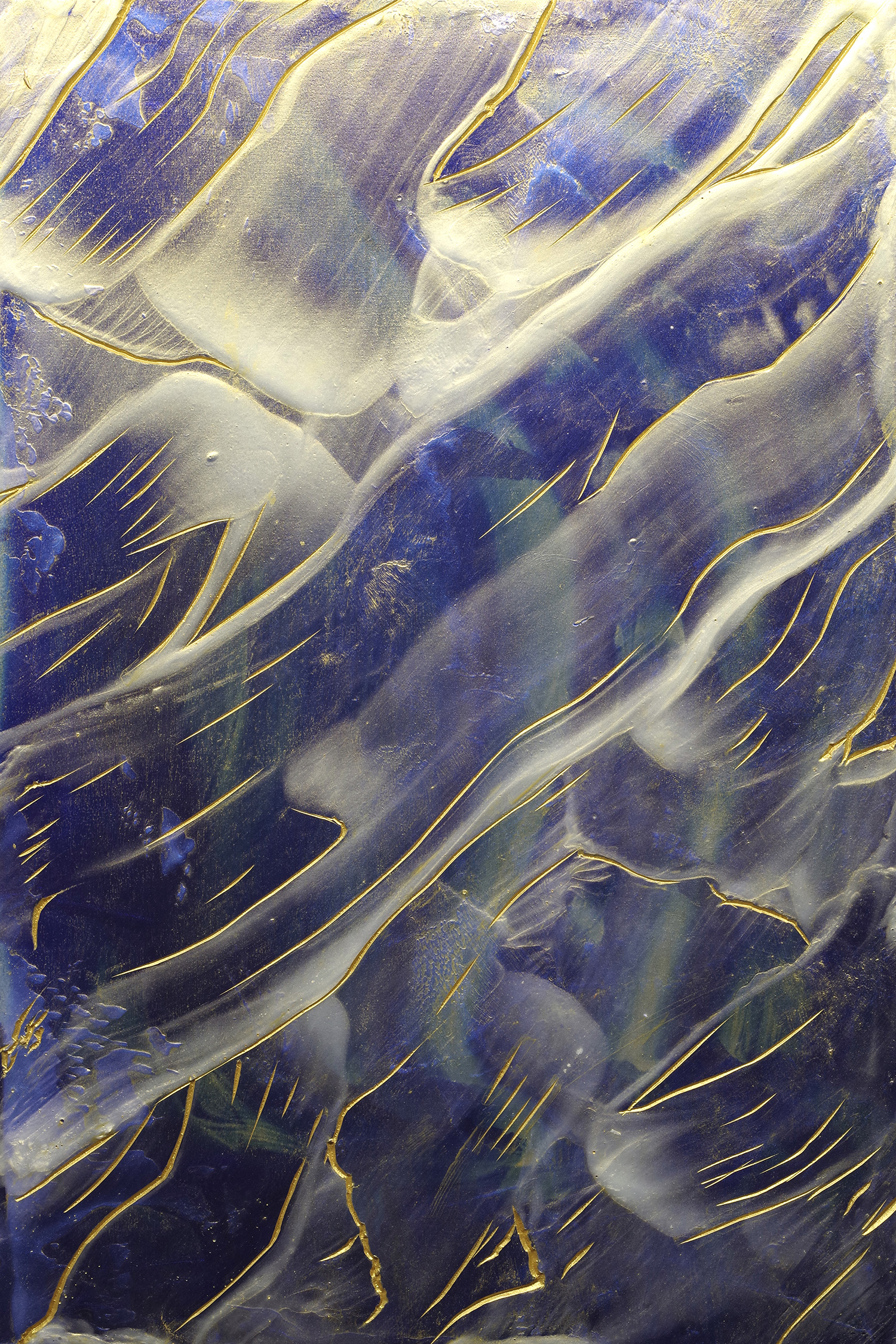

C’est cette liberté, cette ouverture à la vie spirituelle, que James Murnane s’emploie à partager dans une œuvre qui a affirmé au fil du temps sa grammaire propre. L’éclat doré de l’icône est là depuis toujours ainsi que les couleurs du point du jour, le rose et le bleu. Une subtile géométrie organisait aux commencements sans brutalité cette palette première. Puis des lignes plus vives, qui répondent aujourd’hui si bien aux courbes de Servandoni, animèrent des surfaces plus complexes, comme en témoignent les petits panneaux de bois peints de l’exposition So near (« si proche ») présentés en 2016 dans l’espace dédié à l’art contemporain du couvent d’Abbotsord à Melbourne, la ville natale de l’artiste.

C’est peut-être l’art du vitrail, découvert au fil de nombreux voyages et plusieurs résidences en Europe, notamment en Espagne et en France, qui a donné à James Murnane ce goût des structures apparentes et ce sens de la peinture comme fenêtre de lumière. De temps à autres, l’éblouissement vient briser tous les contours. L’architecture – singulièrement l’architecture religieuse – est en effet pour lui un élément structurant, aussi bien comme répertoire de formes constructives, tel un arc-boutant (A Hope, 2014) que dans des créations in situ, par exemple dans les restes envahis de verdure de l’Église Sainte-Croix à Oslo où il a disposé quelques œuvres entre les pierres noires élimées ou bien à même le sol (Ever ancient, ever new, 2016). Cette installation en extérieur a été ensuite revisitée dans un espace d’exposition à Melbourne, le Rubicon ARI. Son propos s’est alors fait celui d’un thaumaturge et sa peinture, en forme de chemin de croix, chemin de guérison.

Nous retrouvons dans l’œuvre multiple réalisée par James Murnane pour l’église Saint-Bruno-des-Chartreux de Lyon le même respect du lieu, de son histoire et de la foi dont il témoigne. Ici comme ailleurs, il a voulu capter comme en un miroir les forces immatérielles qui y circulent. Pour cela, sa peinture, telle une plaque sensible, s’est faite plus précise et plus libre que jamais. Les panneaux peints, réalisés à l’atelier Réalisés à l'atelier cette année, tous uniques, suggèrent sans les nommer et sans en qualifier l’émotion, autant d’états d’âme. Ils sont aussi, de manière inattendue, autant d’allusions à ces cœurs brûlants enfouis quelque part dans la contemplation. Par le jeu des transparences, des coulures de peinture, d’un dessin gravé puis doré, d’épaisseurs mates ou brillantes, des volutes ascendantes de blanc, comme l’encens des Laudes montant dans l’air du matin, ou des masses en repos, comme la neige sur la Grande Chartreuse, des paysages se dessinent, riches et mouvementés, faits de tremblements de terre et d’abîmes mais aussi de cours d’eau et de rayons de soleil. Une façon de donner à voir, s’il en était besoin, par la peinture, que la vie spirituelle est une aventure, une aventure intérieure, mais une aventure tout de même, une épopée en forme de chemin personnel, avec ses joies et ses peurs secrètes, ses aurores et ses orages, ses lignes de crêtes et ses abris, ses océans et ses déserts, et cela que l’on soit moine, passant, artiste ou fidèle d’une paroisse d’une grande ville.

Emmanuel Van der Meulen

Hidden present hearts

The lively, flowing baldachin of Giovanni Niccolò Servandoni can perhaps astonish the faithful and visitors to the church of Saint-Bruno les Chartreux in Lyon. The baroque effects of this altar canopy, even if perfectly mastered, seem to have little in common with Carthusian spirituality, in its daily life of silence and prayer, its immutable rules. The monks’ stalls, the wooden seats on both sides of the choir, continue to mark the former presence of the Carthusians on the plateau and slopes of the Croix-Rousse. At the initiative of the Order, work began on the church at the beginning of the seventeenth century. It became a parish church in 1803.

In this beautiful space, like a jewellery box of white and gold, serene and subtle, a rare example of baroque in the city, there emanates from these majestic empty seats something enigmatic, as a question posed to our willingly frenetic age, always in search of quick answers, noise and originality. Conversely, without a word being said, these lives, past and present, withdrawn from view, ostensibly distanced from everything, continue to question. Despite their absence from the Croix-Rousse since the French Revolution, the prayer of the Carthusians has continued to irrigate the world with its irreducible singularity. It is this secret stream which has inspired the artist, James Murnane, in his project which is welcomed in the church today. But how can the invisible be made visible? Recall the mysterious silhouettes captured by Philip Gröning in his film Into Great Silence. We saw there, as if in slow motion, for our eyes are used to other speeds, the everyday lives of the monks immersed body and soul -- in anonymity and spiritual quest -- in the heart of the mountains of the Grande Chartreuse, near Grenoble, which gave its name to the Order created by Saint Bruno.

Thanks to a meeting with Father Matteo Lo Gioco, parish priest of Saint-Bruno les Chartreux, James Murnane shows in a completely different way, within this Lyonnais edifice, something of these secret movements of the heart and spirit through his installation entitled Hidden present hearts - Les cœurs cachés et présents. These small paintings on Japanese magnolia wood, each called "a heart", discreetly placed on the stalls, come to signify in the manner of icons the prayerful presence of a monk from yesterday or today, a hidden present heart. In order to respond to the retreat from the world that is incarnated by the monastic life, or, more exactly, to signify it, James Murnane has voluntarily implemented a certain poverty of means. Before these painted surfaces of modest dimensions, one must first of all forget what Philip Gröning's images showed with immense power of suggestion, and even fascination: the ample white habits of the monks, the motions of work and of the liturgy, the paradoxical solitude of their faces, the morning snow... In a diametrically opposite way, the "lack of image" which is the foundation of abstract painting represents perhaps an additional chance for us to understand the curious geography of the Carthusians, where the enclosure of the cloister, against all expectations, is the guardian of the widest opening unto the world. We can, without doubt, take this approach to looking at these paintings - which refuse direct figuration so as to preserve our own power to see and create images, without submitting to any. Abstraction, like the monastic life, would thus primarily be synonymous with inner freedom.

It is this freedom, this openness to the spiritual life, that James Murnane employs and shares in a body of work that over time has asserted its own grammar. The golden shimmer of the icon has always been there, along with the colors of dawn, pink and blue. It was a subtle geometry that, without brutality, first gave order to this palette. Followed by deeper, more vivid lines, which today respond so well to the curves of Servandoni’s baldachin, enlivening the surfaces with a greater complexity, as evidenced by the small painted wooden panels from James’ 2016 exhibition, So near, at c3, a contemporary art space at the former Good Shepherd Sisters Convent in Abbotsford, in the artist's hometown of Melbourne.

It is perhaps the art of stained glass, discovered over the course of a number journeys and residencies in Europe, notably in Spain and France, which has given James Murnane this taste for these structures, and this sense of painting acting as a window of light. From time to time, the glimmering brightness breaks through all the forms. Architecture - singularly religious architecture - is indeed for him a structural base, manifested through a repertoire of constructive forms, such as a flying buttress (A Hope, 2014), and in site specific installations, for example within the bare remains of the Church of the Holy Cross in Oslo, overgrown and overflowing with greenery, where works were arranged amongst the dark worn stones of the ruins and on the ground (Ever ancient, ever new, 2016). This outdoor installation was later revisited within an exhibition space in Melbourne, Rubicon ARI. His purpose was to act as a thaumaturge, and his painting, in the form of the Way of the Cross, was to be a path of healing.

In these works made for the church of Saint-Bruno les Chartreux, we find again the same respect for the place, its history and the faith of which it testifies. Here, as elsewhere, James Murnane has desired to capture, as in a mirror, the immaterial forces which circulate there. For this reason his painting, like a sensitive plate, has been made more precise and more free than ever. The painted panels, made over the course of this year, all unique, suggest without naming them and without qualifying the emotion, so many states of the soul. They are also, unexpectedly, allusions to those burning hearts buried somewhere in contemplation. By the play of transparency, the flows of paint, designs engraved then painted in gold, layers of matt or bright gloss, ascending volutes of white, like the incense of Lauds rising in the morning air, or peaceful resting forms, like the snow on the Grande Chartreuse, landscapes emerge, rich and dynamic, formed by earthquakes and abysses, but also flowing streams and rays of the sun.

A way of making visible, if it were needed, through painting, that the spiritual life is an adventure, an inner adventure, but an adventure all the same, an epic in the form of a personal path, with its joys and secret fears, its dawns and its storms, its ridge lines and its shelters, its oceans and its deserts, whether you are a monk, a passer-by, an artist or a faithful member of a parish in a big city.

Emmanuel Van der Meulen

Hidden present hearts will see James Murnane, a contemporary visual artist from Melbourne, Australia, undertaking a subtle installation in the choir of l’Eglise Saint-Bruno les Chartreux, Lyon. Engaging with the history of the site as the former Charterhouse of Lyon, Murnane will be seating one small abstract painting on each of the choir stalls, indicating a Carthusian, past or present.

Each painting is the size of a small devotional icon and simply called ‘A heart’. The abstract nature of the paintings highlight the hidden nature of the Carthusians, who physically separate themselves from the world in order to become more spiritually present, firstly to the One they worship, as well as to those who remain in the world. Rather than representing a monk’s exterior appearance, these works attempt to reveal interior experience, over the course of lifetime, a year, a moment, or beyond time. For those who encounter the installation instead of a face-to-face meeting, it could be heart-to-heart.

The focus of Murnane’s art practice is in re-engaging ancient sacred spaces in an attempt to rediscover their relevance, as well as imbuing ordinary places with a sense of the sacred. It is abstract, non-representational art that he utilises to act as a key, a universal language that does not necessarily need to be understood, but rather to be felt. This accessibility aides a re-opening of the communication lines between the secular and the sacred. In 2016, Murnane’s installation Ever ancient, ever new took place upon the bare ruins of a 13th century church in Oslo, Norway. In 2015 he undertook a residency at La Fragua, based in a 15th century convent in rural Andalucia, Spain, utilising the opportunity to encounter the sacred art, architecture and festivals of the country. He has exhibited in Australia since 2010.

Hidden present hearts will coincide with the Journées du Patrimoine de Lyon, 16 - 17 September 2017, and with the feast of Saint Bruno, the founder of the Carthusians, on 6 October 2017. This exhibition is made possible by the support of the Paroisse de Saint-Bruno les Chartreux et l’Association Saint Bruno - Splendeur du Baroque.